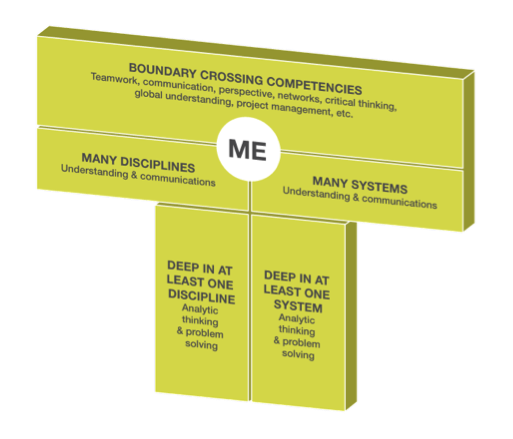

This recommendation starts from our recognition that the University has a responsibility to prepare its students to flourish as informed, skilled, and effective members of their society and of the world. To ensure that we meet this responsibility, the Commission recommends an ambitious new undergraduate curricular framework that balances disciplinary training, developed through the major, with interdisciplinary exploration while strengthening our students’ sense of community. We should provide an education broad as well as deep, one resembling (to use language current in educational studies) a “T,” rather than an “I.[1]” As depicted in Figure 4.1, T-shaped education affords students with the opportunity to develop deep disciplinary knowledge in at least one area as well as the competencies associated with forming connections between disciplines that allow them to become adaptive innovators.

Currently, the University uses “distribution requirements” to ensure interdisciplinary breadth of academic experience. These requirements stipulate that students must earn a minimum number of credits in academic areas outside of their primary major. These areas include humanities (H), natural sciences (N), social and behavioral sciences (S), quantitative and mathematical sciences (Q), and engineering (E). Courses are assigned an area designator by the academic department, if taught within a Homewood academic department; if not taught within a Homewood academic department, they are assigned by the appropriate dean’s office.

Data and anecdotal evidence both suggest that these requirements are not successful. The means by which courses are evaluated for designation is unclear and inconsistent. In some departments, a significant percentage of classes required for the major can also be counted toward the distribution requirement. In KSAS, students can triple count a course toward a major requirement, a writing requirement (“W”), and a social science or behavioral science (“S”) or a Natural Science (“N”)/ quantitative and mathematical science (“Q”)/Engineering (“E”). This thwarts the distributional intent of the requirements. Students majoring in Psychology, for instance, can satisfy 92% of the distribution and writing requirements through major courses alone. The current distribution system does not ensure that students are learning enough about other disciplines to make meaningful connections between and across these disciplines.

To begin our discussion of curricular revision, Commission members reflected matters of principle and articulated the foundational abilities a Hopkins undergraduate education should inculcate.

We continued our curricular discussion by studying models developed by peer institutions. The disquietude found in the reports issued has several sources difficult to detangle: an uncertainty about the relationship between liberal arts education and vocational/pre-professional training; a worry that the “open” curriculum has become a hodge-podge, box-checking exercise; and a concern that a highly-structured “core” curriculum is too rigid for the present needs of students in an increasingly fluid, rapidly altering society.

In their report, Columbia asks several questions of its curriculum: “Are what some have called the ‘containers’ of our undergraduate curriculum appropriately sized? We probably agree that a strong undergraduate curriculum should include general education (our core), specialist education (our majors) and opportunities for exploration (electives). Do we provide ample opportunity for all three of these goals?” Stanford has asked whether the intellectual breadth of a more “open” curriculum serves its undergraduates well. “Few people question the value of intellectual breadth … [but is ‘sampling’] the optimal way of fostering true breadth in an age like ours, in which the boundaries of different fields are increasingly blurred?”

Stanford’s answer to questions like these has been not to prescribe courses in particular disciplinary areas but to promise the acquisition and development of seven “essential capacities,” which foster “ways of thinking, ways of doing.” The capacities they list are aesthetic and interpretive inquiry, social inquiry, scientific analysis, formal and quantitative reasoning, engaging difference, moral and ethical reasoning, and creative expression. They have started to implement this shift in approach by establishing a first-year curriculum experience called “Thinking Matters.” It seeks to inculcate a broadly applicable orientation to academic study rather than narrower forms of knowledge.

Other universities have issued similar statements. U-C Berkeley has said that its graduates should possess four core “competences” and four “dispositions.” Graduates should be literate, numerate, creative, and investigative–these are the competences; and also open-minded, worldly, engaged, and disciplined–the dispositions. UC-Berkeley invokes vocational pressures in justifying its new approach: “students must prepare for fluid careers in a future where what you know is less important than how you think, learn and discover on your own.” To do this, UC-Berkeley aims to “bring greater meaning and coherence to core requirements,” in part by using new technology. For example, they are now using a planning tool called “Course Threads,” which helps students (with faculty supervision) chart a “logically connected sequence of breadth courses.”

Like Stanford and Berkeley, Washington University acknowledges the importance of articulating the essential skills and competences the university wishes its graduates to possess, but it emphasizes the even greater need to cultivate a longer list of “metacognitive skills and attitudes.” These include an ability to think and act creatively, an ability to engage in both individual and collaborative research, an understanding of how knowledge is created and transmitted, the ability to integrate knowledge from several domains, resilience and the ability to adapt to change, intellectual curiosity; practical insight, and “a facility for making normative assessments as well as with establishing matters of fact.” The challenge is how to instantiate these abstract goals in the curriculum. American University, for example, is tackling “quantitative literacy, writing, and information literacy training” by creating a variation on the core curriculum. It is putting in place a five-course sequence emphasizing skill/competency-oriented learning (e.g. “Quantitative Literacy I”). This is supplemented with an optional set of one-credit professional skills modules.

As the Commission studied these varied models, members came to see that a new curricular framework could also address our need to strengthen students’ sense of community, without constraining the curricular freedom they rightly value. Hopkins undergraduates choose to learn across a wide variety of settings and contexts–from the classroom to the residence hall; from the laboratory to the athletic field; from the library to the internship site. This diversity is one of our great strengths. The curricular framework we propose provides a common, shared vision for students as they accumulate a richly varied experience. The foundational abilities we describe would be developed in all of these contexts, through both individual work and in teams, in brief and in extended projects, through an array of programs, courses, and experiences. The abilities would provide a common, shared vision for students as they accumulate a richly varied, independently designed education.

The proposed curricular framework has the following components:

We begin with a pedagogical form invented at Hopkins—the seminar. The Commission recommends that every entering student be required to participate in a first year seminar. Requiring participation in a first year Hopkins seminar would be transformative. At a minimum, the first year seminar would set the tone for the undergraduate experience by providing students with a shared introduction to university life and the opportunity to work closely with senior faculty as they explore scholarly topics. The seminars would also provide opportunity for students to begin developing the foundational abilities. Fully maximized, a first year seminar curriculum could exploit Hopkins’ distinctive combination of small size and unparalleled research faculty while targeting development of particular foundational abilities.

CUE2 reviewed several successful first-year seminar programs, including those developed by Amherst College, Stanford University, the University of Toronto, and UC Berkeley. Amherst’s First-Year Seminars, initially designed as one-year, interdisciplinary courses co-taught by faculty from two different disciplines, are an integral part of the college’s curriculum and required of all students. The First-Year Seminars are now a semester long, and often taught by a single faculty member. The Commission preferred more collaborative and interdisciplinary models that permit students to explore a single theme/topic/problem in depth by exposing them to various modes of inquiry and thus to understand their area of focus from several, overlapping (and sometimes opposed) perspectives. In such courses, faculty model how to comprehend and address complex problems through interaction with peers in other disciplines. UC-Berkeley is experimenting with “Big Ideas” courses taught by faculty from different disciplines and usually across divisions/schools. A course on “Time”, for example, is taught by a philosopher and a string theorist whereas a course on “Origins” is co-taught by a paleontologist, an astrophysicist, and a Biblical scholar. Another model is “Duke Immerse”: students join a cohort and spend an entire semester exploring a single “issue” (e.g. Uprooted/Re-routed: the Ethical Challenges of Displacement”) from an array of disciplinary perspectives. It is “delivered as one cohesive whole occupying the entirety of a student’s academic work for a given semester.”

For the past several years, Hopkins has offered 40 to 50 freshman seminars each academic year in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. These 1-3 credit small classes, usually limited to about 10-15 freshmen, explore specialized scholarly topics chosen by faculty. As noted in Figure 4.2, 33% of freshmen completed a freshman seminar in academic year 2018-19. As an initial step, the Commission recommends 100% participation in a first year seminar for all freshman and transfer students in the first semester that they matriculate. In order to achieve this goal, the University would need to double the number of freshman seminars currently offered, ensuring that they are taught by senior faculty and aligned in terms of credit hour assignment and overarching outcomes.

| Semester | Number of Freshman Seminars Taught | Number of Students Enrolled (percent of class) |

| Fall 2018 | 27 | 297 (23%) |

| Spring 2019 | 10 | 131 (10%) |

| Fall 2019 | 32 | 317 (23%) |

Once this target it achieved, additional options for a more robust first year seminar curriculum should be explored and piloted. For example, the first year seminars could begin to more specifically target the development of expository writing skills by pairing disciplinary expertise from senior faculty with writing instruction expertise from expository writing faculty. This evolution would require extensive consultation and collaboration among faculty, students, staff, as well as the Deans and Provost.

The Commission offers the following as a more long-term, aspirational model for the first year seminars. Every entering student would enroll in a seminar, taught by a faculty member, designed in relation to a shared theme. Each year’s theme would be broad, allowing faculty members flexibility in designing their seminars. The themes would recur, allowing faculty to return to and revise their seminars across the years. In conjunction with these seminars, regular public assemblies would gather new students to hear lectures by visiting scholars and public intellectuals on the year’s theme. Finally, regular sessions with writing instructors would establish the importance of writing in all our disciplines.

In this model, each incoming class (of roughly 1300-1450 students) would be divided into two groups (A and B), which would then cycle through course activities at different times. Each student would attend four public lectures, four seminars (limited to 15 students), and a minimum of four writing discussions (again, limited to the same 15 students) across the semester, as described in Figure 4.3.

| Semester Week | “A” Cycle Activities | “B” Cycle Activities |

| 1 | Shriver Plenary | |

| 2 | Seminar | Shriver Plenary |

| 3 | Writing Group | Seminar |

| 4 | Shriver Plenary | Writing Group |

| 5 | Seminar | Shriver Plenary |

| 6 | Writing Group | Seminar |

| 7 | Shriver Plenary | Writing Group |

| 8 | Seminar | Shriver Plenary |

| 9 | Writing Group | Seminar |

| 10 | Shriver Plenary | Writing Group |

| 11 | Seminar | Shriver Plenary |

| 12 | Writing Group | Seminar |

| 13 | Writing Group |

Were the University to follow this model, the demands on physical space and infrastructure would include the following. Eight times a semester, 750 students would gather in Shriver Hall, and perhaps elsewhere, were lectures to be livestreamed. Every third week, 100 seminar rooms would be needed to accommodate the seminars and writing sessions. (Were students divided into three, rather than two, cycles, the demand on seminar rooms would drop to 67 every third week.) The demands on personnel would include the cost of recruiting eight speakers, assuming each lectured only once. Up to 100 faculty members would be required to lead the four seminar meetings each semester. Again, these faculty would come from the professional schools as well as Homewood, furthering the university’s One University initiative. Themes aligned with JHU’s interdisciplinary institutes and initiatives, including 21st Century Cities and the Agora Institute, would allow us to draw on their resources. The Commission recommends that the Provost’s investment in this initiative should include an innovation competition that provides grant funding for course development. The DELTA (Digital Education & Learning Technology Acceleration) Grant program is an encouraging model. Selecting broad themes–akin to those being chosen for the Common Question experience–would allow faculty latitude to design seminars that engage them; cycling through themes on a regular schedule–say every three years–would allow faculty to return to, and revise, their seminars.

Research has been the core of Hopkins’ identity. One benefit such research has traditionally offered to some of our students is the in-depth experience of extended, immersive study. But this opportunity should be extended to our students, whether in creative activity, professional exploration, or research. To that end, CUE2 proposes to create a “Hopkins Semester.”

The Commission conceives of this program as a junior or senior year, semester-long, mentored, immersive experience that will give students the time for a focused, deep, and rigorous exploration of one complex subject or endeavor either inside or outside their major department. The Commission expects that students themselves will be the driving force of these experiences–that they will propose and complete innovative projects that we don’t presently imagine. If the first-year courses described above in Recommendation 1a would be driven by the intellectual excitement of faculty given the opportunity to teach small seminars, the Hopkins semester would similarly be driven by the passions of the students. But students would be required to provide, and departments required to approve and assess, proposals for and reports on their experience that demonstrate the knowledge, skills, and abilities developed.

Team-based, projects would also be possible. Such projects, whether creative or research-intensive, would develop the skills associated with communication on teams whose members bring distinct qualifications and play interdependent roles. Design projects, artistic endeavors, research projects, commercial ventures, professional internships, and community-based projects all could serve the ends of this recommendation–whether undertaken in the opera house, the archives, Congress, the laboratory, the community center, a startup venture, or the clinic. Pursuing one’s Hopkins Semester abroad would also be encouraged.

This intensive semester should facilitate a high-level synthesis of concepts and practices learned during students’ first and second years of coursework. The Hopkins Semester could satisfy the requirements of some core major courses (and perhaps upper-level courses as well), but need not. In addition, projects and activities before and after this semester could expand and extend the experience. Thus, for example, a project pursued intensively during the semester may be defined and developed before the semester and the activity may continue, albeit at a less intense level, after the semester. (Note that the Hopkins Semester would be immersive: projects completed piecemeal across semesters would not qualify.) The guidance provided by faculty is an essential element of this recommendation, in part because it encourages mentorship. The Hopkins Semester could regularly be a transformative immersive experience—thus furthering one aim already established by the Office of Integrative Learning and Life Design.

In 1998, the Boyer Commission issued 10 recommendations for improving undergraduate education at research universities in the USA; the first recommendation was that research-based learning become standard. Following the Boyer Commission’s lead, several US research organizations—including the Mellon Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation—have funded opportunities to include undergraduates in the research programs of science faculty and, to a lesser extent, those of humanities faculty. Many subsequent studies have demonstrated the benefits of undergraduate research experiences. “Evidence from an array of quantitative and qualitative studies supports the promise of undergraduate research as a catalyst for student development across disciplines, genders, and ethnicities. While cost factors, including money, time, and faculty priorities, need be considered during the creation of an undergraduate research program, the benefits to students are consistent with our greater expectations for liberal learning.[2]” Undergraduate students who completed a mentored research program identified many areas from which they benefited including the interpretation and analysis of data, the ability to work independently and to integrate theory and practice; they also reported greater self-confidence and a clearer understanding of their career paths[3]. But the benefits of such experiences are not limited to research programs; creative and experiential projects can have analogous results.

In 2018, 62% of Johns Hopkins seniors reporting participating in research in the Senior Survey, increased from 57% in 2016. Results of those surveys also suggest that students are generally satisfied with the opportunities to participate in research with a faculty member. The University presently supports undergraduate research in various ways, through the Provost’s Undergraduate Research Award (PURA) (see Appendix I for 2017-19 Metrics), the Woodrow Wilson Undergraduate Research Fellowship Program, the Dean’s ASPIRE Grant (in KSAS), and smaller initiatives, including the library-based program, The Freshman Fellows. But research experience is inconsistent across campus. We excel at supporting student research in the lab but not in the library: In 2014, only 19% of humanities students reported participating in research with a faculty member, and only 27% of social/behavioral sciences students reported doing so; this compared to 59% for natural sciences and 69% for engineering. As our investment in undergraduate research increases, support like that presently offered through PURA and the Dean’s ASPIRE Grant should become more visible and more generously funded.

Of our peers, only Princeton requires a capstone project for all undergraduates; it takes the form of a senior thesis. Others, like Stanford, make a point of encouraging all seniors to complete capstones. Some capstone experiences offered elsewhere resemble the Hopkins Semester we propose. George Mason University offers research semesters in biology. The University of Michigan offers a Humanities Collaboratory that brings together faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate research assistants over a semester. Duke offers an intensive research semester with seminars called DukeImmerse, a cohort model in which students spend an entire semester exploring a single issue from an array of disciplinary perspectives. Like the Hopkins Semester, DukeImmerse is one cohesive whole occupying the entirety of a student’s academic work for a given semester. It involves daily interaction with faculty members and a collaborative project. About four such programs run each semester. Similarly, the “Immersion Vanderbilt” program encourages students to pursue creative and/or independent projects. The program is “inherently flexible to allow the student to work closely with a faculty mentor on a project that provides a depth of experience.” Finally, standalone programs, like EUROScholars, enable students to use a study abroad semester for research.

For the Hopkins Semester to be viable within our traditional four-year program, departments will need to ensure that the sequencing of their courses allow for a full semester immersive experience. Additionally, advising services would need to assist arranging projects undertaken on campus and, in coordination with advisors in majors and career services, also assist arranging projects undertaken off-campus. The Undergraduate Education Board would be charged with developing best practices in setting learning objectives and assessment expectations for the Hopkins Semester. Departments will use those guidelines to develop student application, approval, and assessment processes. The Board should also establish baseline expectations regarding faculty mentoring of students based on best practices.

Integrative learning is an understanding and a disposition that a student builds across the curriculum and co-curriculum, from making simple connections among ideas and experiences to synthesizing and transferring learning to new, complex situations within and beyond the campus.[4]

Student learning is not contained by the architecture of formal coursework; the rewards of co-curricular and extra-curricular activities are distinctive, various, and essential to any undergraduate education. Our students pursue their passions, apply their learning, and connect with alumni, community leaders, and other Johns Hopkins affiliates outside as well as inside the classroom. In short, they should integrate their various experiences into a distinctive education.

We are well positioned to transform the college experience from one composed solely of traditional elements—lectures, papers, problem sets, and exams—to one in which these elements sit amid a much broader range of learning activities within and beyond the classroom. The many benefits of this transformed experience would be varied. A plan to develop such a fully integrated experience at Hopkins has already been initiated by the Office of Integrative Learning and Life Design. Central to that plan is the development of a co-curricular roadmap that integrates coursework, intersession and summer experience, community activities, and social networks to ensure that all students are exposed to the same rich opportunities. This education would include tools for students to document, reflect on, and assess all their educational activities, and would help them lay the groundwork for life-long learning and their post-graduate careers. To support this initiative, the Commission recommends that the Undergraduate Education Board develop clear policies on awarding credit or credential based on learning outcomes for structured co-curricular experiences relevant to disciplinary study. Linking outcomes to academic requirements would send a powerful signal to faculty and students concerning the importance of co-curricular learning. Such a policy would also guide faculty as they facilitate student reflection on their extramural work and evaluate their experience against outcomes defined by the program and University.

“The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) has long promoted integrative learning for all students as a hallmark of a quality liberal education, noting its essential role in lifelong learning” (National Leadership Council for Liberal Education and America’s Promise, 2007). Increasingly, integrative learning is recognized as an empowering developmental process through which students synthesize knowledge across curricular and co-curricular experiences to develop new concepts, refine values and perspectives in solving problems, master transferable skills, and cultivate self-understanding. An AAC&U-sponsored project on integrative liberal learning between 2012 and 2014 with fourteen small liberal arts institutions has helped illuminate a variety of practices that strengthen connections across learning experiences and encourage students to reflect on their goals with the aim of making intentional curricular and co-curricular choices, charting their own progress, and understanding the ‘why’—and not just the ‘what’—of their four years.”[5]

Data concerning students’ participation in extra- and co-curricular activities at Hopkins are scattered. In the 2016-2017 academic year, Johns Hopkins University had 409 student organizations (including fraternities and sororities). Currently, there are 395 student organizations, and this number is expected to surpass 400 as the year progresses, given organizations that are currently going through the process of being established. In the 2016 Senior Survey, 63.1% of students reported having participated in at least one student organization (including fraternities and sororities) during their time as an undergraduate. As noted in Appendix H, participation varies across majors.

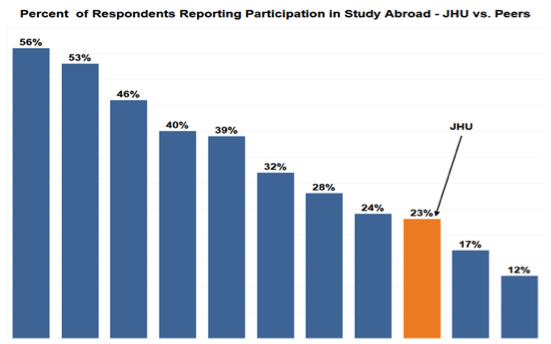

Figure 4.4 reveals that 23% of 2018 Senior Survey respondents reported studying abroad, a low rate among our peers. In the same survey, students also reported that they would have liked to spend more time involved in extracurricular activities, volunteering, relaxing, and socializing.

Data about JHU sponsored off-campus activities are harder to ascertain, but the numbers appear quite low: 3.0% of students have participated in off-campus activities sponsored by the Office of Student Leadership and Involvement, for instance; 2.4% have participated through the Center for Social Concern.

Other universities, including Boston University and University of South Carolina, have created models for integrating co- and extracurricular activities into student experience, and created infrastructure to enable, document, and reward those activities. Among the most robust of these models is the 21st Century Badging Challenge developed by the Educational Design Lab in association with public and private universities in the Washington D.C. area. Engaging faculty members and about 40 students from each participating institution, the program determines rigorous assessment criteria for its badges, in order to present a comprehensive signal to employers about student achievement. The University of South Carolina (USC) has developed the USC Connect program, which provides learning pathways that start in the first year, take students outside of the classroom, and enable them to create substantive portfolios. Successful students graduate with “leadership distinction” designated on their diplomas and transcript. Finally, the University of Mary Washington and Emory University have both piloted projects to provide a personal web space to all incoming students; in this space, students will develop integrated, holistic e-portfolios that include both curricular and co/extra-curricular evidence of their activities.

Again, some of the resources for a more fully integrated learning experience at Hopkins are already at hand. The Center for Social Concern (CSC) has been particularly active in encouraging students to engage with the Baltimore community. CSC supports both extra-curricular engagement, through hosting student organizations, and curricular experiential learning opportunities, through a faculty fellows program. The CSC’s France-Merrick Civic Fellowship allows students to undertake community work. In collaboration with the Whiting School of Engineering’s Center for Educational Outreach, CSC helps sponsor the Charm City Science League, an organization of over 100 student volunteers who work with teams of middle-school students to prepare for Science Olympiad and robotics competitions.

Implementation plans for the development of a more fully integrated undergraduate experience have already been formed by the Office of Integrative Learning and Life Design. Features of that plan include embedding career staff in academic programs and communities; replacing career services with scalable life design programs that integrate coursework, connections, and experiential learning; developing learning modules for staff and faculty on life design; creating dynamic websites, online platforms, and a digital presence; and drafting a narrative of life design for admissions, departments, centers, and alumni relations. Departments should be charged with developing policies for the assessment of co-curricular activities where warranted, in consultation with the Undergraduate Education Board. The University’s new learning assessment platform provides an opportunity to develop Comprehensive Learner Records for each undergraduate student. These records are digital, official documents issued by the institution that provide a richer expression of the learning outcomes or competencies mastered during a student’s experience than traditional transcripts and diplomas as they capture course-based, co-curricular, and extracurricular learning.

The above three recommendations (1a-c) are intended to prepare students with foundational intellectual skills and dispositions for lifelong learning. But these foundational abilities must also be incorporated into the design of major curricula and courses. Majors require that students know a segment of human knowledge deeply, and master its ways of thinking. They also require that students integrate foundational abilities in a specific field of study. Many of the foundational abilities will be cultivated in courses required for the major; others may be cultivated through other coursework; still others, importantly, may be cultivated through co-curricular activities. To that end, the Commission recommends that the current distribution requirements be modified to become distribution areas that correlate with the foundational abilities. All students will be required to take a minimum of one course in each of the six distribution areas by the time of graduation. Further, the deans of KSAS and WSE charge each department with evaluating and modifying existing curricula and designing new curricula that ensures that their majors are trained in each of these abilities.

Each academic department will be required to demonstrate to the Undergraduate Education Board that their students will develop the foundational abilities all Hopkins students should acquire by mapping major program outcomes and course learning objectives to the foundational abilities and distribution areas. Multifaceted assessment of program outcomes and learning objectives will provide students, departments, and schools with formative and summative data that illustrate students success in achieving the abilities. Such data should be evaluated by the department regularly to inform the need for curricular revision and appropriate allocation of resources.

CUE2 recognizes that this recommendation will require academic departments to develop much more sophisticated and robust means of assessing students’ knowledge, skills, and abilities as well as evaluating courses and programs. However, this shift is necessary if we truly want to encourage an educational culture that promotes development of competencies rather than accrual of credentials. Modifying the current distribution requirement system alone would only perpetuate a credential gathering, box-checking approach to undergraduate education. It is imperative that revision of that system occur concomitantly with a shift in culture within our academic departments. With support from the deans, the academic departments must bear the primary responsibility for ensuring that students achieve both the breadth and depth of intellectual inquiry outlined.

The six new distribution areas, reflective of the six foundational abilities, also provide opportunity for academic innovation. Faculty should be encouraged to develop new courses that span disciplinary boundaries, thereby targeting development of skills on the horizontal bar of the “T.” For example, a competitive academic innovation fund could be established to develop new classes that require students to apply their disciplinary knowledge in the context of a team composed of students with varied expertise from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds. Several models already exist within our university upon which the infrastructure for such courses could be built. Several engineering departments already engage industrial partners to sponsor student projects, while the Center for Social Concern builds connections between extracurricular student projects and Baltimore communities. The recently pioneered Classics Research Lab provided a mechanism for a team of students to undertake a reconstruction of the contexts of and influences upon the work of Victorian scholar John Addington Symonds, author of one of the first major studies of Ancient Greek sexuality, pioneering a humanities-centric approach to problem based learning. A pilot to teach Multidisciplinary Engineering Design is underway in Fall 2019 during which 18 students from across 6 engineering majors are engaged in 4 different projects with external partners. These range from investigating microfiber separation from wastewater in collaboration with sportswear manufacturer Under Armour, to engaging with social enterprise Clearwater Mills to develop innovative ways to engage the communities that live around Professor Trash Wheel to improve the effectiveness of this installation to prevent trash from entering the Baltimore Harbor. And in 2018 a Hack Your Life Design Challenge engaged 18 teams of students from Mechanical Engineering at JHU and the Maryland Institute College of Art. Teams had to use at least five different materials to create an interactive project with moving parts that cost no more than $100. The challenge provided students with the freedom to explore different ways in which engineering and art can intersect.

The pathways students take to meet the distribution areas requirement and to develop the foundational abilities will be widely varied, and driven by their individual interests and needs. CUE2 recognizes that their success will require careful advising and mentoring by faculty, staff, peers, and others. Recommendation 4 below describes a new system of advising, mentoring, and coaching, which would provide the support needed for this new curricular framework. Certainly, the burden of ensuring that students acquire these foundational abilities will be considerable. But the curricular framework described here highlights one great strength of our university: that it provides students with a combination of unmatched institutional resources and individual attention. This vision aims to ensure that all our students benefit from that distinctive strength while enrolled, and flourish after they graduate.

[1] T-Academy (2018) http://tsummit.org/t

[2] Lopatto, D. (2006). Undergraduate research as a catalyst for liberal learning. Peer Review, 8(1), 22-25. See also: Gillies, S. L., & Marsh, S. (2013). Doing science research at an undergraduate university. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 6(4), 379; Hempstead, J., Graham, D., & Couchman, R. (2012). Forging a template for undergraduate collaborative research: A case study. Creative Education, 36(Special Issue), 859-865; Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2009). Developing undergraduate research and inquiry (p. 152). York: Higher Education Academy; Kuh, G. D. (2008). Excerpt from high-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities, 19-34; Lopatto, D. (2010). Undergraduate research as a high-impact student experience. Peer Review, 12(2), 27.

[3] Lopatto, D. (2010). Undergraduate research as a high-impact student experience. Peer Review, 12(2), 27

[4] Rhodes, T. L. (2010). Making learning visible and meaningful through electronic portfolios. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 43(1), 6-13.

[5] Ferren, A. S., & Anderson, C. B. (2016). Integrative learning: Making liberal education purposeful, personal, and practical. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2016(145), 33-40.; see also Kehoe, A., & Goudzwaard, M. (2015). ePortfolios, badges, and the whole digital self: How evidence-based learning pedagogies and technologies can support integrative learning and identity development. Theory Into Practice, 54(4), 343-351.