Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Students should be able to count on the significant, positive presence of faculty, staff, and administrators from matriculation to graduation and beyond. In our vision, each undergraduate student would have an integrated group of, at least, a faculty mentor, an academic advisor, and a career coach; this group would remain connected to that student throughout their undergraduate career. The provision of these support teams will require a redesign and revitalization of academic advising services, integrating it more deliberately with career services and with faculty mentoring. Because students build cohorts through their affinity for topics and passions for interests, mechanisms should be implemented to facilitate better alignment with, and maintenance of, the relationships among students, alumni, faculty, staff, and graduate students who share passions and affinities. Providing this support infrastructure will also require creation of and investment in faculty mentoring programs.

We understand mentorship to be distinct from advising in both purpose and execution. Mentors help students develop interests, affirm identities and achieve life goals. Mentors include staff, alumni, peers, and community partners, but the central role is played by faculty members, who serve as mentors best simply by sharing their intellectual enthusiasm. To be sure, students must be active participants in seeking out and building their own mentor relationships. But faculty members should expect to serve as mentors, and the University should actively encourage and support them as they do serve. Because courses most naturally initiate mentoring, the University should increase the number of small courses—research seminars, discussions, collaboratories—that enable substantial relations among teachers and students.

As noted in the introduction to this section of the report, the timing of these initiatives is fortuitous, coinciding with the launching of the Office of Integrative Learning and Life Design; that office has already begun to implement several of the advances described below. Additionally, we will have the benefit of our participation in the Excellence in Academic Advising initiative, launched in coordination with NACADA, a national organization of academic advisors, and the Gardner Foundations. Along with several other committees, this pilot program is assessing the preconditions for successful academic student support in KSAS and WSE. A full and detailed report is expected later this year and an implementation plan to follow. This guidance should be afforded the highest priority, so that academic advisors can be properly provisioned to support each student’s successful navigation of the various choices involved in academic life, from course selection to choosing their major and minor areas of study, to ensuring development of the foundational abilities and completion of a Hopkins semester, to tapping into university resources to sustain health, well-being and fulfillment, to seeking help when unforeseen challenges arise.

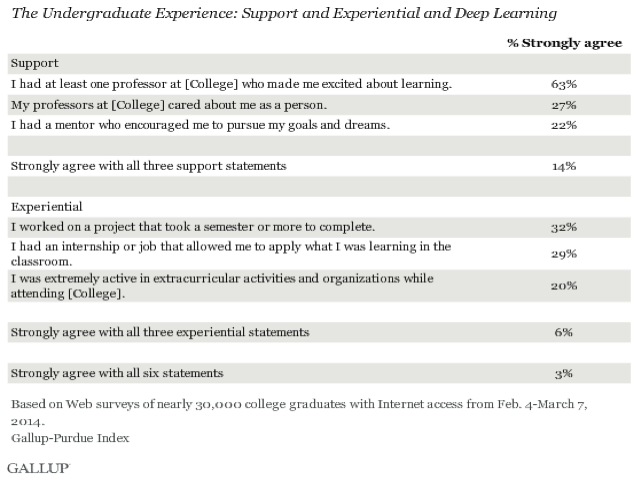

Most, perhaps all, of the experiences linked by the Gallup-Purdue Index Inaugural National Report (shown in Figure 4.13) concerning post-collegiate satisfaction with college depend upon mentoring: having at least one professor who excited the student about learning; having professors who cared about the student as a person; having a mentor who cared about the student’s hopes and dreams; having worked on a project that took a semester or more to complete; having an internship or job that helped the student apply what he or she was learning; being extremely active in extracurricular activities. More, importantly, mentoring has been shown to be effective in increasing the persistence of non-traditional students.[1] The benefits of better integrating academic advising and career counseling has also been urged by scholars for the past several decades.[2]

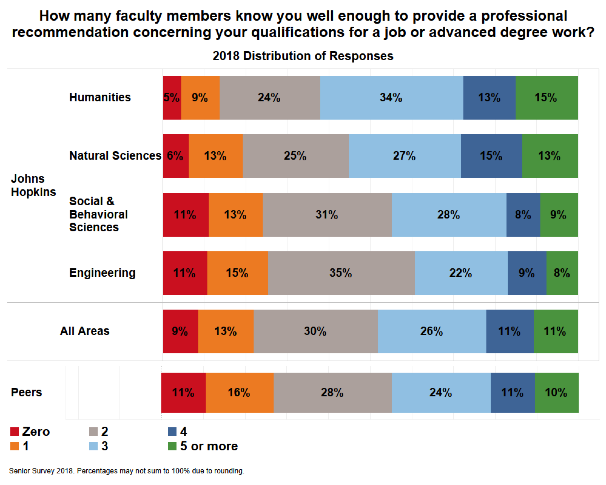

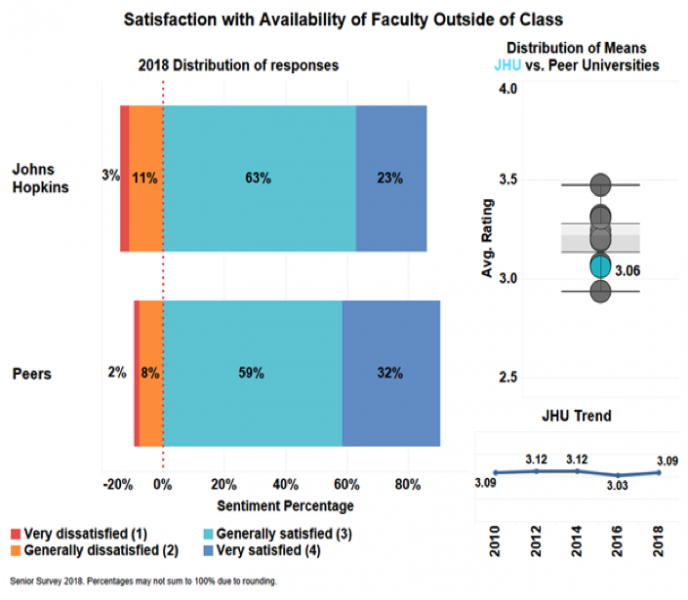

As depicted in Figure 4.14, 22% of 2018 Senior Survey respondents reported that they know no professor, or only one professor, well enough for them to provide a professional recommendation. This figure is higher than ideal. All students should know more than one professor who could write them a letter of recommendation. The numbers vary across our schools and fields. Students in the humanities fare better than those in the sciences and engineering: 14% of humanities students report that they know at most one faculty member sufficiently to ask her for a recommendation; in social and behavioral sciences the figure is 24%; in engineering the figure is 26%. In the same survey, 86% of Johns Hopkins respondents were satisfied with faculty availability, versus 91% at peer schools, a significant difference. Humanities respondents were significantly more satisfied than others (see Figure 4.15).

Advising models vary widely among our peers, and few appear to have partnered faculty mentoring, academic advising, and career counseling in the way envisioned by CUE2; Hopkins has an opportunity to lead in this area. Of note, University of Chicago assigns a four-year academic advisor and career coach, as well as a PhD student, to each undergraduate upon admission. Perhaps the closest model is James Madison University, which has merged its academic advising and career center into a single advising unit, enabling the integration of academic and career plans, and providing a model that students intuitively understand. This should be our goal, too.

[1] Bettinger, E. P., & Baker, R. B. (2014). The effects of student coaching: An evaluation of a randomized experiment in student advising. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(1), 3-19.

[2] McCalla-Wriggins, B. (2009). Integrating career and academic advising: Mastering the challenge. NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources.